When you walk into a pharmacy and pick up a generic version of your blood pressure pill, you might assume the price is low because there are lots of companies making it. That’s usually true-but not always. In fact, the number of generic manufacturers doesn’t always mean lower prices. Sometimes, having more competitors actually keeps prices high. This isn’t a glitch. It’s how the system works under the surface.

More Generic Competitors Don’t Always Mean Lower Prices

The FDA says that when six or more generic companies make the same drug, prices drop by about 95% compared to the brand-name version. That sounds great. But in reality, most drugs never reach that level of competition. A 2023 study in China found that 70% of originator drugs had only one or two generic makers, even years after the first generic entered the market. Why? Because getting approval isn’t the same as getting into the market.

For simple pills-like metformin or lisinopril-dozens of companies can make them cheaply. But for complex drugs, like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams, the barriers are huge. You don’t just need the right chemicals. You need to prove your product behaves exactly like the brand in the body. That means expensive testing, specialized equipment, and regulatory reviews that can take years. Only big generic manufacturers with deep pockets can handle it. So even if 10 companies get approval, only 2 or 3 actually sell the drug. That’s not competition. That’s a controlled market.

The Paradox of Generic Drug Competition

Here’s something counterintuitive: brand-name companies sometimes raise prices after generics enter the market. It sounds crazy, but it happens. In China, researchers found that 3 out of 27 brand-name drugs actually increased in price after generics arrived. Why? Because the brand still had loyal customers who believed it was better. Maybe it had fewer side effects. Maybe doctors trusted it more. So the brand company didn’t fight the price drop-they just raised the price for the few people still buying it.

This is called the ‘paradox of generic competition.’ The brand doesn’t need to win the price war. It just needs to keep a small, loyal slice of the market at a higher price. Meanwhile, the generics fight over the rest. The result? The overall market price doesn’t drop as much as it should.

How Pharmacy Benefit Managers Change the Game

Most people think pharmacies set drug prices. They don’t. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) do. These middlemen negotiate bulk deals between drugmakers and insurers. By 2017, PBMs controlled 90% of all drug purchases in the U.S. That means they hold all the power. If a PBM wants to push a cheaper generic, they can. But if they have a deal with the brand company-like a rebate for keeping the price high-they might not push the generic at all.

That’s why a drug with five generic competitors might still cost the same as the brand. The PBM isn’t pushing the generics because they’re getting paid to keep the brand on the formulary. It’s not about competition. It’s about contracts.

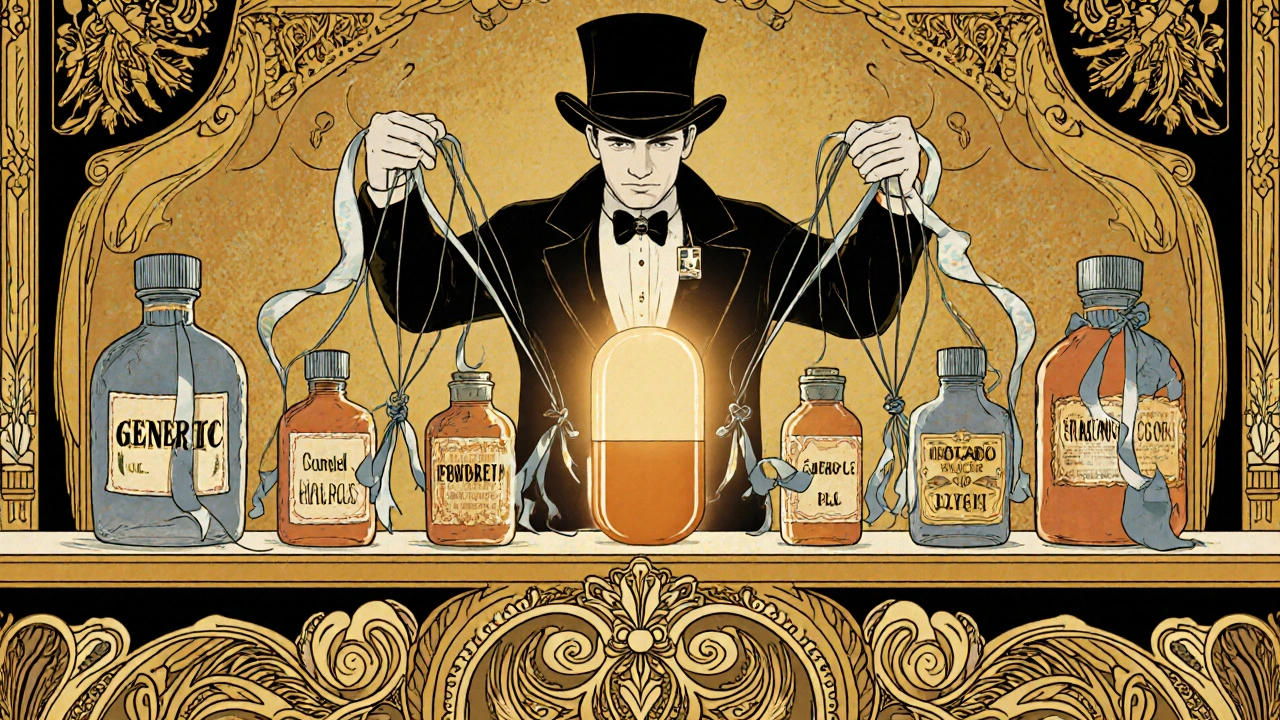

Authorized Generics: The Secret Weapon

Some brand-name companies don’t wait for competitors to enter. They make their own generic version and sell it under a different name. These are called authorized generics. They’re identical to the brand, but cheaper. And they hit the market during the first 180 days of generic exclusivity-the period when the first generic company has a legal monopoly.

Here’s the twist: if the brand company owns the authorized generic, wholesale prices drop by 8-12%. But if a different company owns it, the brand’s price jumps by 22%. Why? Because the brand company feels threatened. It knows the authorized generic isn’t helping it-it’s helping someone else. So it raises its own price to make up for lost ground.

This isn’t competition. It’s corporate chess.

Price Caps and Mutual Forbearance

In countries like Portugal, the government sets a maximum price for each drug. Sounds fair, right? But it backfires. When all companies know the ceiling, they don’t compete to undercut each other. They just price right at the cap. It’s called mutual forbearance. No one wants to be the first to drop the price, because then everyone else will follow. So prices stay high, even with five or six generic makers.

This isn’t collusion. It’s rational behavior under regulation. The system meant to lower prices ends up freezing them.

Patent Games and Pay-for-Delay Deals

Brand-name companies don’t just rely on science. They rely on lawyers. They file dozens of patents-not just on the drug, but on its coating, its shape, its packaging, even how it’s taken. Each patent creates a new hurdle for generics. A generic company might win approval for one version, only to get sued over a patent they didn’t even know existed.

Worse, some brand companies pay generic makers to stay out of the market. These are called pay-for-delay deals. The brand pays the generic company millions to delay launching. The FDA estimates these deals cost U.S. consumers $3.5 billion a year in higher prices. They’re legal in the U.S., though banned in the EU. And they’re still happening.

Supply Chains and Shortages

Here’s one place more competitors actually help: keeping drugs in stock. Between 2018 and 2022, the FDA found that drugs with three or more generic manufacturers had 67% fewer shortages than those made by just one company. Why? Because if one factory shuts down, another can pick up the slack. But if only one company makes a drug-say, a cheap antibiotic or a thyroid pill-and their plant has a problem? The drug disappears. People go without. Hospitals scramble.

That’s why the real value of competition isn’t just lower prices. It’s resilience. A market with multiple makers is harder to break.

The Inflation Reduction Act and the New Threat

In 2022, the U.S. passed the Inflation Reduction Act. One part lets Medicare negotiate prices for some brand-name drugs. That sounds good-but it has an unintended side effect. If Medicare caps the price of a brand drug at $100, why would a generic company spend $5 million to get approval and build a factory to sell it for $80? There’s no profit. No incentive.

Drugmakers are already cutting back on production for drugs that might be price-negotiated. That means fewer generics entering the market. Less competition. Fewer options. The very system meant to lower costs could end up strangling generic entry.

Why Some Drugs Never See Real Competition

Not all drugs are created equal. Oncology drugs like imatinib or dasatinib often have huge price gaps between brand and generic-but still, few generics enter. Why? Because these drugs are complex. They’re given in hospitals. Doctors are cautious. Patients are scared. The brand has trust. The generic has a label.

Chronic disease drugs-like those for diabetes or high cholesterol-are different. They’re taken daily. Patients switch easily. Prices drop fast. But for drugs where trust matters more than cost, competition stays weak.

What Does This Mean for Patients?

If you’re on a generic drug and the price suddenly jumps, it’s not random. It could be a PBM changing its deal. Or a brand company raising its price for loyal customers. Or the only manufacturer running low on supply.

If your drug keeps running out, it’s likely made by only one company. Ask your pharmacist: ‘Is there another generic version?’ If they say no, it’s probably because no one else is making it.

And if your insurance won’t cover the generic, even though it’s cheaper? That’s probably because the PBM is getting a kickback from the brand.

The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed. But it’s designed to protect profits, not patients.

What’s Next for Generic Competition?

The next wave of competition isn’t going to be about pills. It’s going to be about biologics-complex drugs made from living cells. These are the new expensive drugs for cancer, autoimmune diseases, and rare conditions. They cost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Generic versions of these are called biosimilars. They’re harder to make. Harder to approve. And so far, they’ve had slow adoption. The FDA says we might not see the same 85% price drop we got with small-molecule generics. That means the next decade could bring even higher drug costs-not lower.

Unless policymakers fix the system-by limiting pay-for-delay, banning price caps that freeze competition, forcing PBMs to pass savings to patients, and supporting small manufacturers-we’re going to keep seeing the same pattern: more approvals, less competition, higher prices, and more shortages.

John Mackaill 21.11.2025

It’s wild how the system is engineered to keep prices high even when competition looks abundant. I never realized PBMs were the real gatekeepers-like, who even are these people? And why do they get to decide what drugs we get access to? It’s not about health. It’s about who’s paying whom.

I’ve seen this firsthand with my dad’s thyroid med. One day it was $12, next month $48. No warning. No explanation. Just a new PBM contract. No one’s accountable.

Jennifer Skolney 21.11.2025

This hit me right in the feels 😔 I’ve been on the same generic blood pressure med for 7 years. Last month, my copay jumped $20. My pharmacist shrugged and said, ‘It’s the PBM.’ I just wanted to cry. How are people on fixed incomes supposed to survive this? 😞

JD Mette 21.11.2025

The part about authorized generics being used as a strategic weapon by brand companies is something most people don’t talk about. It’s not just about price-it’s about control. The system rewards manipulation over transparency. And the worst part? It’s all legal.

Patients aren’t dumb. We notice when the same pill suddenly costs more, even if the label says ‘generic.’ But no one explains why. We’re left guessing, frustrated, and powerless.

Olanrewaju Jeph 21.11.2025

It is important to recognize that the structural flaws in the pharmaceutical supply chain are not accidental; they are systemic. The convergence of regulatory capture, patent trolling, and PBM monopolization creates a perfect storm that disincentivizes true market competition. Small manufacturers are systematically excluded due to capital requirements and legal threats. This is not capitalism-it is corporatized rent-seeking disguised as free enterprise.

Furthermore, the Inflation Reduction Act, while well-intentioned, inadvertently disincentivizes generic entry by capping prices without ensuring cost-sharing mechanisms for manufacturers. Without subsidies or risk mitigation for small producers, innovation will continue to concentrate in the hands of the few. Policy must shift from price control to market access.

Additionally, the global supply chain fragility exposed during the pandemic underscores the necessity of diversified production. Relying on one or two manufacturers for essential medicines is a public health crisis waiting to happen. Governments must incentivize domestic and regional manufacturing capacity, not just negotiate lower prices.

Lastly, biosimilars represent the next frontier. If we replicate the same flawed model-patent thickets, pay-for-delay, PBM gatekeeping-we will repeat the same mistakes. Regulatory agencies must prioritize biosimilar approval timelines and enforce transparency in rebate structures. Otherwise, the next generation of life-saving drugs will remain unaffordable.

Dalton Adams 21.11.2025

Look, most people don’t understand the difference between a generic and a biosimilar, and that’s why this whole system is collapsing. You think metformin is complicated? Try explaining why a monoclonal antibody can’t just be copied like a pill. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards for small molecules are laughably simple compared to the 12-year, $500M nightmare of biosimilar development.

And don’t get me started on PBMs-they’re not middlemen, they’re oligopolistic parasites. They take 15-20% of the drug’s list price as a ‘rebate’ and call it a ‘discount.’ That’s not a discount-that’s a tax on patients. And yes, I’ve read the Congressional Budget Office reports on this. I’ve read the GAO audits. I’ve read the JAMA studies. You’re all just repeating headlines.

Also, ‘authorized generics’ aren’t some secret weapon-they’re a legal loophole exploited since the 1980s. The Hatch-Waxman Act was supposed to fix this. Instead, it became a playbook for brand companies to game the system. The real villain? The U.S. patent system. We grant patents on everything from pill color to dosing schedules. It’s not innovation. It’s legal extortion.

And before you say ‘just regulate it,’ remember: every regulator is either a former pharma exec or a future one. The revolving door is wider than the Grand Canyon. So no, I’m not holding my breath for ‘policy fixes.’ The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed. And it’s designed to make billionaires richer while you pay $500 for insulin.

Kane Ren 21.11.2025

I know this sounds crazy, but I actually believe things are getting better-even if it’s slow. More people are talking about this now. More lawmakers are asking questions. More pharmacists are pushing back on PBMs. And patients? We’re finally starting to speak up.

Remember when people thought generic drugs were ‘inferior’? Now, most doctors prescribe them without hesitation. That shift took decades. But it happened. We can do the same for biosimilars and fair pricing.

It’s not hopeless. It’s just complicated. And complicated things take time. But we’re on the right path. Keep pushing. Keep asking. Keep sharing stories like this one.

Charmaine Barcelon 21.11.2025

So let me get this straight… you’re saying the drug companies are LYING to us?!?! And the government is LETTING them?!?! And the pharmacy middlemen are STEALING our money?!?! And we’re just supposed to SIT HERE and PAY?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THIS COUNTRY?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!?!

Karla Morales 21.11.2025

📊 Data point: In 2023, 82% of drugs with 5+ generic manufacturers still had a median price within 12% of the brand. This isn’t competition-it’s price anchoring. PBMs extract 18-22% of the list price as ‘rebates,’ but patients never see a dime. The system is a tax on necessity.

📉 The 95% price drop myth? It only applies to 3% of all generic drugs. The rest? 1-3 manufacturers. The FDA’s ‘6+ = 95% drop’ metric is a statistical outlier used to mislead the public. It’s not a policy goal-it’s a PR slogan.

💉 Biosimilars are the next battleground. But if we don’t fix PBM transparency and patent abuse now, we’ll see the same pattern: 10-year delays, 15% market penetration, and 70% price retention. This isn’t innovation. It’s exploitation with a science degree.

Javier Rain 21.11.2025

I’ve worked in community pharmacies for 15 years. I’ve seen patients skip doses because the price jumped. I’ve watched people cry because they had to choose between insulin and rent.

But here’s the thing-we’re not powerless. We can ask for alternatives. We can call our reps. We can demand transparency from our insurers. And we can support local pharmacies that push back on PBM rules.

It’s not just about the system. It’s about what we do with the little power we have. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask why your med costs more. Demand to know if there’s another generic. That’s how change starts.

One voice at a time. One question at a time. We’ve got this.

Laurie Sala 21.11.2025

Why do I even bother taking my meds anymore? I just sit here and stare at the pill bottle and wonder if I’m going to die because some corporate lawyer decided I’m not profitable enough to live.

I hate this. I hate that I have to beg for my own health. I hate that I’m supposed to be grateful for a $10 generic when the brand is $400. I hate that my body is just a spreadsheet to them.

Someone please tell me how to fix this. Or just tell me to give up. Either way, I’m tired.

Lisa Detanna 21.11.2025

What’s fascinating is how this mirrors global patterns. In Nigeria, where I’m from, we see the same thing-brand companies use authorized generics to crush local manufacturers. The FDA’s rules are copied worldwide, and suddenly, a small African producer can’t compete because they can’t afford the 18-month regulatory review.

But here’s the twist: in places like India and Brazil, generic manufacturers have found ways to innovate-using open-source chemistry, community labs, and public-private partnerships. They don’t wait for permission. They just make it happen.

Maybe the answer isn’t more regulation. Maybe it’s more empowerment. Support local generics. Demand transparency. Don’t just accept what’s handed to you. We can build better systems-if we stop waiting for someone else to fix it.

John Mackaill 21.11.2025

That last comment about Nigeria and Brazil? That’s the spark we need. We’re so focused on fixing the U.S. system, we forget that the rest of the world is already doing it differently-and better. Why can’t we learn from them? Why do we think our broken model is the only way?

Maybe it’s time to stop begging for reform and start building alternatives. Community co-ops. Public manufacturing. Open-source drug development. We don’t need permission to imagine a better system.