What Is Ulnar Neuropathy?

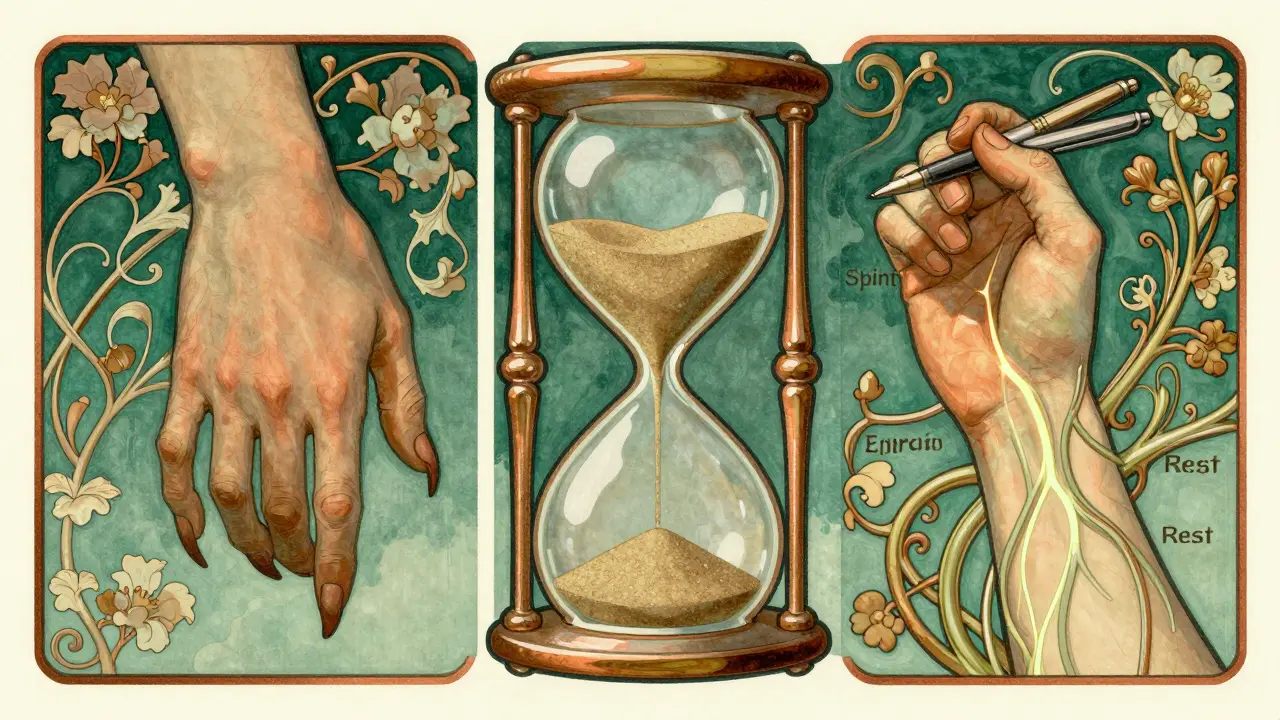

Ulnar neuropathy is a condition where the ulnar nerve - one of the three main nerves in your arm - gets squeezed or compressed, leading to numbness, tingling, and weakness in the hand. This nerve runs from your neck down to your little finger, passing through tight spaces at the elbow and wrist. When it’s pinched, it doesn’t send signals properly, and that’s when you start feeling symptoms.

The ulnar nerve controls sensation in your little finger and the outer half of your ring finger. It also powers the small muscles in your hand that let you grip things, pinch, and spread your fingers. If this nerve stays compressed for too long, those muscles can start to waste away. That’s why early action matters - once muscle loss happens, it’s hard to reverse.

Where Does the Nerve Get Trapped?

There are two main spots where the ulnar nerve gets squeezed. The most common is at the elbow, called cubital tunnel syndrome. This happens behind the bony bump on the inside of your elbow - the medial epicondyle. The nerve here has almost no padding. Lean on your elbow too much, or keep it bent for hours, and it’s like sitting on a garden hose.

The second spot is at the wrist, known as Guyon’s canal syndrome. This is less common but still significant. Here, the nerve passes through a narrow tunnel made of ligaments and bones near the base of your palm. Ganglion cysts, fractures, or repetitive pressure from tools or handlebars can squeeze it here.

About 90% of ulnar nerve issues happen at the elbow. That’s why so many people notice symptoms when they sleep with their arms bent under their head, or while driving or talking on the phone.

What Do the Symptoms Feel Like?

Symptoms usually start mild and get worse over time. At first, you might feel occasional tingling in your ring and little fingers - especially when you bend your elbow. You might shake your hand out, like you do when your foot falls asleep. That’s the nerve saying, "Hey, cut that out."

As it progresses, the tingling becomes constant. You might feel a dull ache along your forearm or hand. Your grip weakens. You drop things. Opening jars or holding a coffee cup becomes hard. You might notice your little finger starting to curl inward - what doctors call a "claw hand." That’s muscle wasting in action.

Many people report symptoms waking them up at night. It’s not just discomfort - it’s a sharp, electric-like pain that makes you jolt awake. Some describe it as if their hand is "on fire" or "numb and heavy."

If you’ve had these symptoms for more than a few weeks, especially with muscle loss or weakness, you’re past the point where rest alone will fix it.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Ulnar neuropathy doesn’t pick favorites, but some people are more likely to get it. Men between 35 and 64 are diagnosed more often than women. That’s partly because of job risks.

Plumbers, mechanics, carpenters, and assembly line workers often keep their elbows bent for long periods. Telephone operators who cradle a headset between shoulder and ear are also at risk. Even cyclists and rowers can develop it from pressure on the handlebars or oar grips.

People who sleep with their arms tucked under pillows or bent behind their heads are more likely to trigger symptoms. It’s not just bad posture - it’s repeated compression over months or years.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t just guess. They start with a physical exam. They’ll tap on the nerve behind your elbow - if that sends a shock down your fingers, that’s a positive Tinel’s sign. They’ll check your grip strength, finger spread, and sensation in your hand.

The gold standard for diagnosis is a nerve conduction study (NCS). This test measures how fast electrical signals move through the ulnar nerve. If the signal slows down at the elbow or wrist, that’s clear evidence of compression. An electromyography (EMG) test can also show if the muscles are starting to weaken from lack of nerve input.

For wrist cases, ultrasound or MRI might be used to look for cysts, tumors, or scar tissue. These aren’t always needed, but they help when the cause isn’t obvious.

Non-Surgical Treatments: What Actually Works?

For mild to moderate cases, surgery isn’t the first step. About 50% of people get better with conservative care - if they stick with it.

Activity changes are critical. Avoid leaning on your elbows. Don’t sleep with your arms bent. Use a headset instead of holding your phone. If you drive a lot, adjust your seat so your elbow isn’t jammed against the window.

Elbow splints are one of the most effective tools. Wearing a padded brace at night keeps your elbow straight. Studies show this reduces nighttime symptoms in over 70% of patients. Some people wear it during the day too, especially if their job forces them to bend their elbow often.

NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen help reduce swelling around the nerve. They won’t fix the compression, but they can ease pain and inflammation, especially in the early stages.

Physical therapy is key. A therapist will teach you nerve gliding exercises - gentle movements that help the nerve slide more freely through its tunnel. Do them 3-4 times a day. They’re not flashy, but they work. You’ll also get strengthening exercises for your hand muscles to prevent further wasting.

Corticosteroid injections are an option if swelling is the main issue. Injected near the nerve at the elbow or wrist, they can shrink inflammation and give you relief for weeks or months. They’re not a cure, but they can buy time to avoid surgery.

Medications like gabapentin or pregabalin are sometimes prescribed for nerve pain. These don’t fix the compression, but they can calm down the abnormal signals causing burning or shooting pain.

When Is Surgery Necessary?

Surgery becomes the best option if you have:

- Constant numbness that doesn’t improve

- Visible muscle loss in your hand

- Weak grip or pinch that’s getting worse

- Failed 3-6 months of conservative treatment

There are three main surgical options:

- Simple decompression - the surgeon cuts the ligament over the nerve at the elbow to give it more room. It’s the least invasive. Recovery is faster - usually 6-8 weeks.

- Decompression with anterior transposition - the nerve is moved from behind the elbow to the front, so it’s less likely to get pinched again. This is often used if the nerve keeps slipping out of place. Recovery takes longer - up to 6 months.

- Medial epicondylectomy - the bony bump behind the elbow is shaved down to give the nerve more space. It’s less common but useful in cases with severe bone spurs or arthritis.

Studies show simple decompression and transposition have similar success rates - around 85-90% of patients see good improvement. But transposition has a higher risk of infection and scarring. Your surgeon will pick the best option based on your anatomy and how long you’ve had symptoms.

Post-op, you’ll start hand therapy in 2-3 weeks. You’ll need to avoid heavy lifting for 6-12 weeks. Full recovery can take up to 6 months, especially if muscles were already weak.

What About Newer Treatments?

There’s growing interest in less invasive options. Ultrasound-guided hydrodissection is one. A doctor uses real-time imaging to inject fluid around the nerve, gently separating it from surrounding tissue. Early results are promising, especially for patients who aren’t candidates for surgery.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections are being tested too. The idea is that your own healing cells can reduce inflammation and help nerve repair. But right now, evidence is limited to small studies. Don’t expect miracles - it’s still experimental.

Endoscopic surgery is another emerging option. Instead of a big cut, the surgeon uses a tiny camera and small tools. Early reports say less pain and faster return to work. But it’s not widely available yet, and not all surgeons are trained in it.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat It?

Ignoring ulnar neuropathy isn’t an option. Nerves don’t heal well once they’re damaged for too long. Muscle atrophy in the hand is often permanent. You might lose the ability to pinch a key, button a shirt, or hold a pen. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s life-changing.

Permanent numbness in your fingers can lead to unnoticed injuries. You might burn your hand on a stove or cut yourself without feeling it. That’s why early diagnosis is so critical. The sooner you act, the better your chances of full recovery.

Can You Prevent It?

Yes - but it takes awareness. If your job or habits put pressure on your elbows or wrists, make small changes:

- Use padded armrests at your desk

- Adjust your chair so your elbows aren’t bent over 90 degrees

- Don’t rest your elbows on hard surfaces

- Use a headset or speakerphone

- Take breaks every 30 minutes to stretch your arms

- Wear a night splint if you sleep with bent elbows

For athletes: cyclists should adjust handlebar height. Golfers and tennis players should check their grip technique. Even small tweaks can prevent long-term damage.

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

With proper treatment, 85-90% of people regain normal or near-normal hand function. Those who catch it early and stick with therapy often recover fully. Even those who need surgery usually see big improvements.

But recurrence happens. About 1 in 8 people who have surgery get symptoms back - usually because the root cause wasn’t fully addressed. Maybe they went back to leaning on their elbow. Maybe they didn’t do their exercises. Or maybe the nerve was already too damaged.

The key is consistency. Don’t stop splinting or doing exercises just because you feel better. Nerve healing is slow. Muscle rebuilding takes time. And prevention? That’s a lifelong habit.

Rosalee Vanness 13.01.2026

I’ve been living with this for years and didn’t even know what it was called. I thought I just had "bad sleeping posture"-turns out I was crushing my ulnar nerve like a soda can every night. Started wearing that elbow splint after reading this, and holy hell, the nighttime electric zaps? Gone. Not cured, but finally manageable. I’m doing the nerve glides three times a day now, even when I don’t feel like it. It’s boring, but it’s working. If you’re reading this and you drop things often or your pinky goes numb when you drive? Don’t ignore it. Your hand isn’t just "tingling"-it’s screaming. Listen.

lucy cooke 13.01.2026

Ah, the ulnar nerve-nature’s most misunderstood poet. A silent bard trapped between bone and sinew, whispering symphonies of tingling to those too deaf to hear. We modern humans, in our relentless pursuit of efficiency, have turned our bodies into factories where nerves are mere wires to be pinched, bent, and ignored until they scream in Morse code through our fingertips. Is this not the ultimate tragedy of the Anthropocene? We build bridges across oceans but cannot spare a millimeter for our own biology. The elbow-once a sacred hinge of rest and contemplation-now a battleground of ergonomic neglect. We are not merely suffering from neuropathy. We are suffering from civilization.

Lethabo Phalafala 13.01.2026

My uncle lost half his hand function because he refused to see a doctor for two years. Said "it was just numbness." Two years. He’s 58 now and can’t hold a fork properly. I cried when I saw him try to button his shirt and his fingers just… curled. This post? It’s a lifeline. If you’re reading this and you feel that weird buzz in your pinky? Go. Now. Get the NCS. Don’t wait for the claw hand. Don’t wait for the fire. Don’t wait until you’re crying in the kitchen because you can’t open a jar. I’m not being dramatic-I’m being real. Your hand is not replaceable.

jefferson fernandes 13.01.2026

Guys-seriously-stop leaning on your elbows! I used to rest my arms on my desk like a lazy cat, and I had numb fingers every morning. I bought a $15 foam elbow pad from Amazon, started sitting upright, and now? Zero symptoms. It’s not rocket science. It’s posture. It’s awareness. It’s not being a sloth. Also-yes, the splint works. I wore it for three weeks, and my nighttime tingling dropped by 90%. No magic pills. No expensive gadgets. Just stop crushing your nerve. And if you’re a cyclist? Raise your handlebars. Lower your saddle. Your ulnar nerve will thank you. And so will your grip.

James Castner 13.01.2026

Let us consider the metaphysical implications of neural entrapment: the human body, a cathedral of electrochemical grace, reduced to a series of vulnerable conduits-each nerve a sacred filament, strung taut between the soul and the world, yet routinely violated by the banalities of modern existence. The ulnar nerve, in its quiet dignity, endures the indignity of desk chairs, phone cradles, and sleep positions born of exhaustion. To suffer ulnar neuropathy is not merely to experience tingling-it is to be reminded, in the most visceral terms, of our fragility. We are not machines. We are not algorithms. We are flesh and fire, and when we ignore the whispers of our nerves, we do not merely neglect a medical condition-we neglect our own humanity. Surgery may restore function, but only mindfulness can restore reverence.

Adam Rivera 13.01.2026

Hey, I’m a mechanic and I’ve got this bad boy in both arms now. Just wanted to say-this post is spot on. I started using padded gloves and switched to a headset at work. Also, I do the nerve glides during lunch. It’s weird, but it helps. And yeah, the splint? I wear it at night. My wife thinks I look like a robot, but she’s the one who reminds me to do it now. We’re both proud of me for not ignoring it. If you’re in a trade job and your fingers are going numb? You’re not alone. And you’re not weak for needing help. We’re all just trying not to lose our grip-literally.

Trevor Davis 13.01.2026

So I read this whole thing and then I cried. Not because I have it-but because I didn’t know how many people are silently suffering. My roommate’s been dropping spoons for months and said it was "just arthritis." I showed him this post. He’s making an appointment tomorrow. That’s the thing-this isn’t just about nerves. It’s about awareness. It’s about people who think pain is normal. It’s about how we’ve been trained to ignore our bodies until they break. I’m not saying this to be dramatic. I’m saying it because I’ve seen what happens when you wait. Don’t wait.

John Tran 13.01.2026

Ok so I had this for like 3 years and i thought it was carpal tunnel but nooo it was ulnar and i was like "why is my pinky always asleep" and then i read this and i was like "ohhhhhhh" and i got the nerve test and it was like "yep your nerve is slower than a snail on vacation" and i got the splint and i do the exercises and its like 80% better but i still drop my coffee cup sometimes and i feel like a zombie but i’m trying. also i typo a lot because my hand is tired. sorry.

mike swinchoski 13.01.2026

Stop being lazy. You think your elbow is too sensitive? Then stop resting it on hard surfaces. You think your phone is too heavy? Use speakerphone. You think sleeping with your arm under your head is comfortable? Then you’re the problem. This isn’t a medical crisis-it’s a personal failure of discipline. Get a splint. Stop being a baby. Your hand doesn’t need pity-it needs accountability. If you can’t be bothered to change your habits, don’t expect the world to fix you.