Kidney Stone Surgery: What to Expect and How to Prepare

A clear guide on what kidney stone surgery involves, how to prepare, what to expect on the day, recovery steps, risks, and practical tips for a smooth return to daily life.

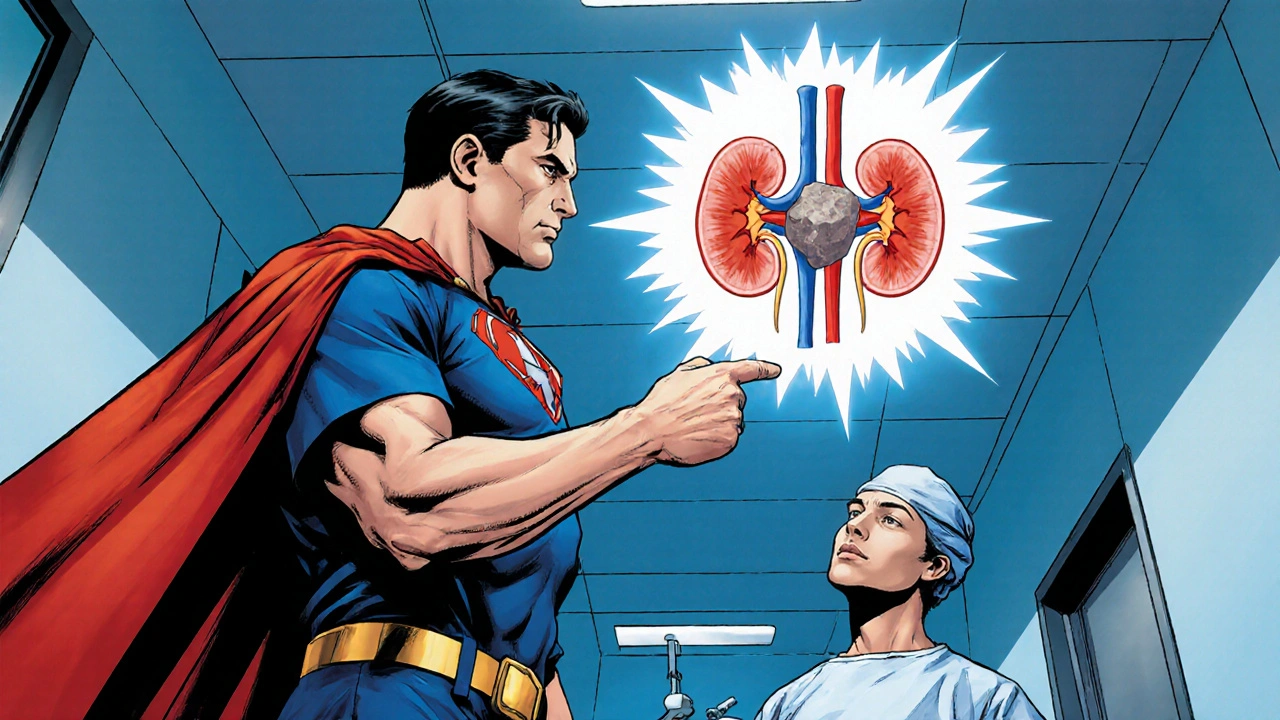

When talking about kidney stone surgery, a set of medical procedures that break down or remove hard mineral deposits from the urinary tract. Also called renal stone intervention, it becomes necessary when stones cause severe pain, block urine flow, or lead to infection. Understanding the why, how, and what‑next of these procedures helps you make confident choices and stay ahead of complications.

Three main techniques dominate the field. Lithotripsy, the use of shock waves to fragment stones so they can pass naturally works best for stones under 2 cm located in the kidney or upper ureter. It’s non‑invasive, usually done outpatient, and relies on imaging to target the stone. Ureteroscopy, a thin scope inserted through the bladder into the ureter to grab or laser‑break stones is preferred for stones lodged lower in the ureter or when lithotripsy fails. Finally, Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL), a small incision in the back that allows direct access to large or hard stones is the go‑to for stones larger than 2 cm or staghorn formations. Each method has distinct advantages, and your surgeon will match the technique to stone size, location, and your overall health.

These procedures all share a common workflow: diagnosis, preparation, the actual intervention, and post‑op care. Diagnosis starts with imaging—usually a non‑contrast CT scan because it shows stone size, composition, and exact location. Accurate imaging guides the surgeon in choosing the right technique and avoids unnecessary tissue damage. Preparation often includes hydration, a brief fasting period, and sometimes medication to relax the urinary tract. During surgery, anesthesia varies from local (for lithotripsy) to general (for PCNL). After the stone is fragmented or removed, a stent may be placed to keep the ureter open while swelling subsides.

Recovery differs by technique. After lithotripsy, many patients go home the same day, need plenty of water, and may see small stone fragments in their urine for a week or two. Ureteroscopy can cause a mild sore throat in the bladder area and occasional blood in urine, which typically clears within a few days. PCNL involves a small incision, so you’ll watch the wound for signs of infection and limit heavy lifting for a few weeks. Pain management usually includes acetaminophen or ibuprofen; stronger painkillers are reserved for the first 24‑48 hours if needed.

Diet and lifestyle also play a big role in preventing new stones after surgery. Knowing your stone’s chemical makeup—calcium oxalate, uric acid, or struvite—helps tailor your diet. For example, limiting salt and animal protein cuts calcium stone risk, while staying well‑hydrated (aim for at least 2‑3 liters of urine‑producing fluid daily) reduces the chance of any stone type forming. Your doctor may prescribe a medication like thiazide diuretics to lower calcium excretion or potassium citrate to increase urine pH for uric acid stones.

Complications are rare but worth mentioning. Infection, bleeding, or injury to surrounding organs can happen, especially with PCNL. Most issues show up within the first week, so keep an eye on fever, persistent pain, or difficulty urinating. Early detection and prompt medical attention keep outcomes favorable.

With this overview, you should have a solid grasp of what kidney stone surgery entails, how each technique works, and what you can do to ensure a smooth recovery. Below you’ll find a curated selection of articles that dive deeper into medication choices, post‑op care tips, and the latest advancements in stone‑removal technology. Keep reading to arm yourself with the practical details that make a difference after your procedure.

A clear guide on what kidney stone surgery involves, how to prepare, what to expect on the day, recovery steps, risks, and practical tips for a smooth return to daily life.